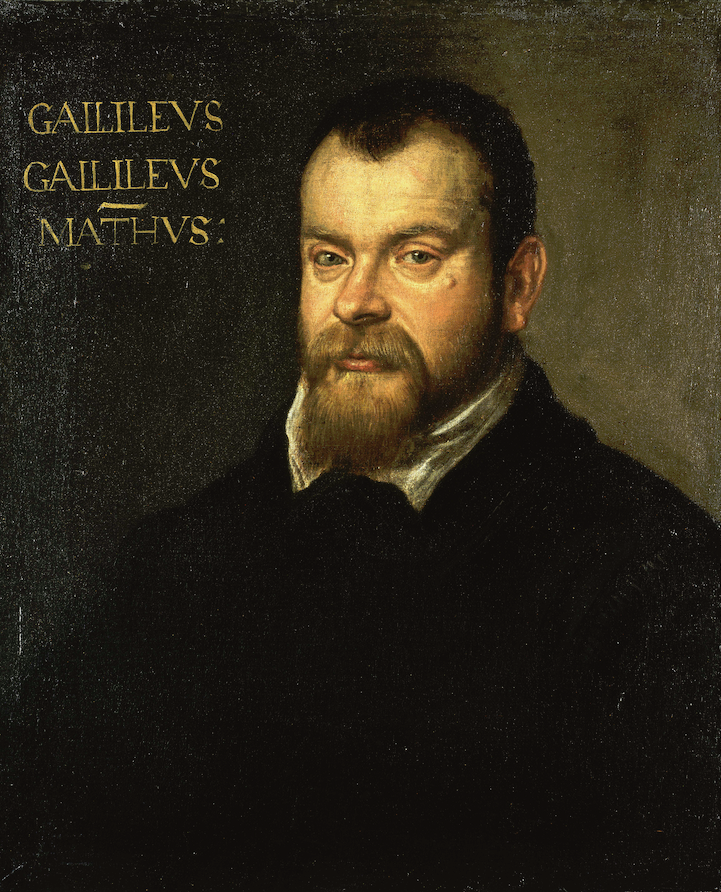

Today, February 15, marks the birth anniversary of Galileo Galilei, a scientist, mathematician, and astronomer who changed how people understood the universe. Born in 1564 in Pisa, Italy, he made groundbreaking discoveries that challenged long-held beliefs. But his work also put him at odds with powerful institutions, leading to a dramatic clash with the Catholic Church (and his former friend Pope Urban VIII).

Galileo’s real breakthrough came when he improved the telescope. He didn’t invent it, but he refined its design, making it powerful enough to study the heavens. In 1609, he pointed it at the night sky and saw something no one had seen before: mountains on the Moon, moons orbiting Jupiter (now called the Galilean moons), and countless stars invisible to the naked eye. In a previous post, I mention that with his telescope, in 1610, was the first human to actually see Venus as more than just a bright point of light in the sky. These discoveries challenged the idea that everything in space was perfect and unchanging, as Aristotle had taught.

His observations supported the heliocentric theory—the idea that the Earth orbits the Sun, not the other way around. This theory, first proposed by Copernicus, was controversial. Many believed Earth was the center of the universe, a view supported by the Church. Galileo’s evidence contradicted this, which led to trouble.

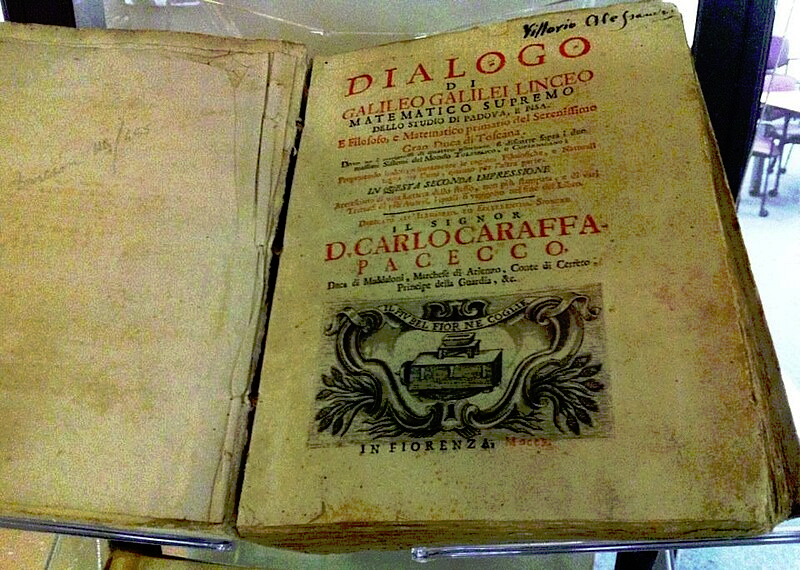

In 1616, the Church warned him not to teach heliocentrism as fact. He obeyed for a while but later published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in 1632, a book comparing geocentrism and heliocentrism. Though written as a discussion, it clearly favored the Sun-centered model. The Church saw this as defiance. Galileo was summoned to Rome, tried for heresy, and forced to recant his views. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

Despite this, he continued working. His later studies on motion and inertia laid the groundwork for Newton’s laws of physics. He also experimented with pendulums and even sketched ideas for a pendulum clock, though he never built one. His contributions to science were so profound that Einstein later called him the “father of modern science.”

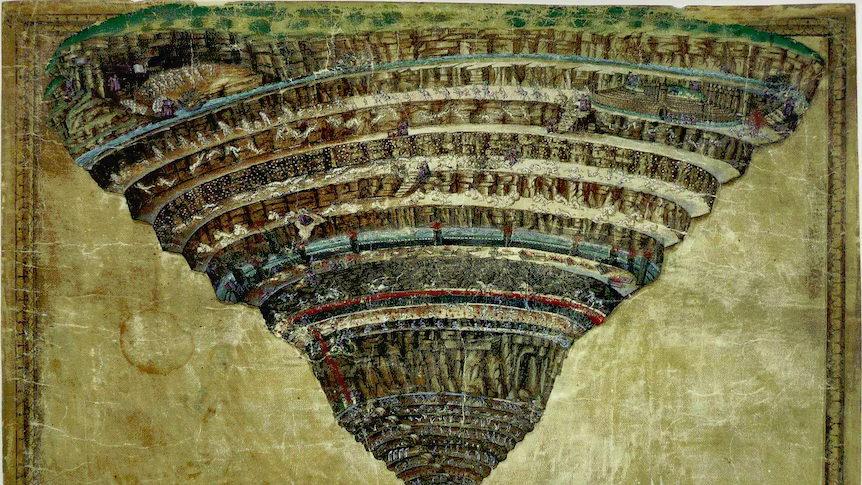

Beyond his scientific achievements, Galileo was known for his sharp wit. Once, when a critic dismissed his findings, he supposedly muttered, “And yet, it moves,” (the Italian expression: Eppur si muove) referring to the Earth’s motion. Another amusing fact: he once wrote a paper on why Dante’s Inferno placed certain sinners at different depths, applying real-world physics to a literary work. Read more here.

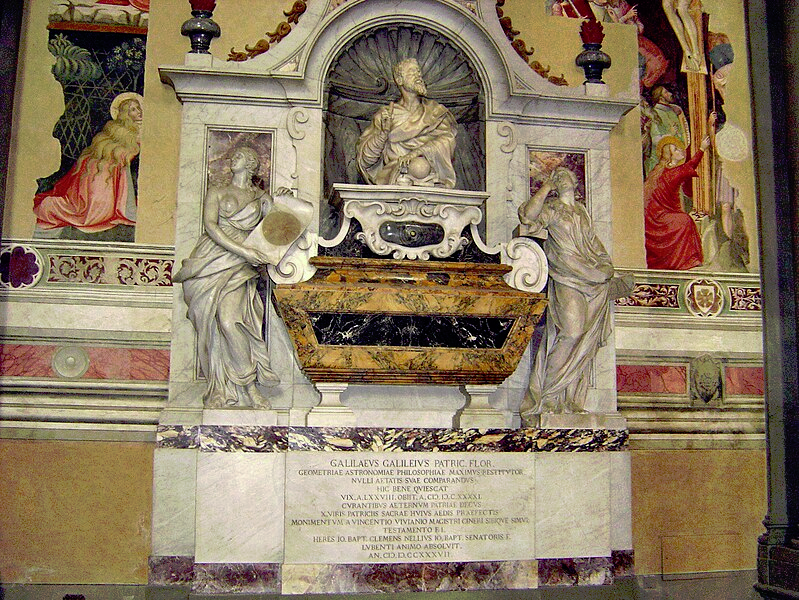

His influence didn’t fade with his death in 1642. Over time, his ideas gained acceptance, and in 1992, Pope John Paul II formally acknowledged that the Church had been wrong to condemn him. Today, Galileo is remembered not only for his discoveries but also for his unwavering commitment to seeking the truth, even when it came at great personal cost.

NASA honored Galileo’s legacy by naming a spacecraft after him. The Galileo spacecraft, launched in 1989, studied Jupiter and its moons for over a decade. It provided groundbreaking data on the planet’s atmosphere, magnetic field, and its largest moons, including evidence of subsurface oceans on Europa. The mission ended in 2003 when the spacecraft was deliberately plunged into Jupiter to prevent contamination of its moons.

His life is a testament to the power of curiosity and reason. He dared to challenge the status quo, he questioned authority, challenged outdated beliefs, and changed the course of science. His legacy lives on in every telescope pointed at the stars, every physics equation taught in classrooms, and every scientist who dares to ask, “What if?”

Science is not about belief; it is a process of continuous discovery and refinement. What we accept as fact today may evolve tomorrow as new evidence emerges. Galileo’s story reminds us that questioning, testing, and adapting our understanding is at the heart of scientific progress.